Men Have Suffered Too

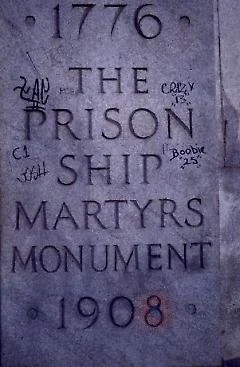

One of the greatest American monuments to human suffering is in Green Park, Brooklyn: The Prison Ship Martrys Monument. It memorializes 11,500 American POWs who died under horrific conditions on British ships---floating prisons---anchored off Long Island during the American Revolution.

One of the greatest American monuments to human suffering is in Green Park, Brooklyn: The Prison Ship Martrys Monument. It memorializes 11,500 American POWs who died under horrific conditions on British ships---floating prisons---anchored off Long Island during the American Revolution.

Every night, guards threw the garbage overboard: the bodies of young American men.

Every nation and people have their suffering stories. They are critical shapers of common identity: nothing is more unifying than we suffer together. But in our country have the suffering stories of some identities been elevated over those of others? And what does that mean for those whose stories have been sidelined?

For twenty-six years I counseled young men at an Ohio community college. Both my Black students and white, for different reasons, had limited awareness of their respective suffering stories. The former because their stories generally lacked firsthand chronicling; but also because such stories were always a problematic fit with the nation’s proud image of itself. But for those students, the needle is moving in the right direction. Despite textbook controversies, the acceleration of history projects nationally to draw back the veil on the suffering stories of Black Americans is robust and multi-faceted.

The young white men I counseled, by contrast, assumed they did not have a justifiable claim to historical suffering. No surprise after enduring years of K through 12 school history lessons which thematically implicate white males as oppressors. For how can oppressors suffer? Or, if they did, it was somehow optional. If white men died of hunger and cold at Valley Forge, it was because they were free to do so.

When I mentioned this marginalizing bias to my faculty colleagues their response was predictable: written history was always only about men---history---so move over! But as Eugene August, a pioneer scholar in Men’s Studies, wrote: “History is about a few men written by a few men for a few men.” We know about the lords of the manor because their portraits still hang in the manor house. But there are no portraits of the tenant farmers who toiled and died on their estate.

That said, a re-balancing to include the experiences of all Americans was always overdue. This was perhaps first set in motion---in spectacular fashion---with the 1974 publication of Bury my Heart at Wounded Knee. Topping the non-fiction bestseller list, in a single stroke it transformed popular perceptions of native Americans as movie bad guys into human beings who suffered. Moreover, for the first time the U.S. Calvary were the bad guys. A radical reversal. But fair.

But must re-balancing be a zero-sum equation? And what is the result when the only stories young white males hear about historical white men are the “oppressor stories”? We don’t know what the effect is on their collective psyches. But we do know, thanks to Women’s Studies, that negative messaging aimed at one gender will be collectively internalized over time.

When working with young men, I attempted, through group and individual counseling, to re-introduce them to “their” suffering stories. One of my most popular sources was the published journal of Private Jos. Plumb Martin, a farm boy who served seven years in the continental army during the American Revolution. Both my Black and white students viewed it for what it is: a young man’s personal narrative of physical hardships. Martin writes: “….if I stepped into a house to warm me, when passing, wet to the skin and almost dead from cold, hunger, and fatigue, what scornful looks and hard words have I experienced.”

Part of my students’ reaction was surprise, a sort of “That actually happened?” But there was also a therapeutic outcome. Attempting to simulate Martin’s many sleepless nights on cold ground, one student tried to sleep in his backyard on a frosty October night, like Martin having only a single woolen layer. He shivered for one hour and went back inside. But he connected with someone else’s suffering from the past, enabling him to appreciate and honor that suffering. More importantly, it helped him realize his own daily struggles were maybe not as bad as he thought.

In the canon of American suffering there should be room for both “Bury my Heart” and Jos. Plumb Martin. When our suffering stories are regulated or politicized, it risks obscuring their true pathos. A human condition we all have in common.